The countries who took part in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 accepted to refrain from using “projectiles the sole object of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases”. These Conventions, however, have been widely ignored and the use of gases in WWI has been recorded as early as 1914.

Chemical warfare was started by France in August 1914, when tear gas grenades (xylyl bromide) were used to slow down the German army advancing through Belgium. Poisonous gas however didn’t appear on the battlefield before April 1915, during the second battle of Ypres, when the German army sent a chlorine cloud against French lines.

Overall, about 124.000 tons of chemical agents have been used during WWI., both lethal and non-lethal. The casualties amount to over 1 million injured and 90.000 dead. Whereas the huge gap between the number of soldiers exposed to gases and the actual amount of fatalities allows to question the effectivenes of such weapon, its brutality is undeniable.

The first “guest” of this episode is Johann Görtemaker, German soldier. In a letter from 26th August 1917 he relates a special tactic used by the enemy in Flanders. The British combined poisonous gas clouds with harmless smoke screens in order to cover their movements and disorient the German army. Listen:

More information on Johannes Görtemaker is available at http://www.europeana1914-1918.eu/de/contributions/462, togehter with a transcription of his letters.

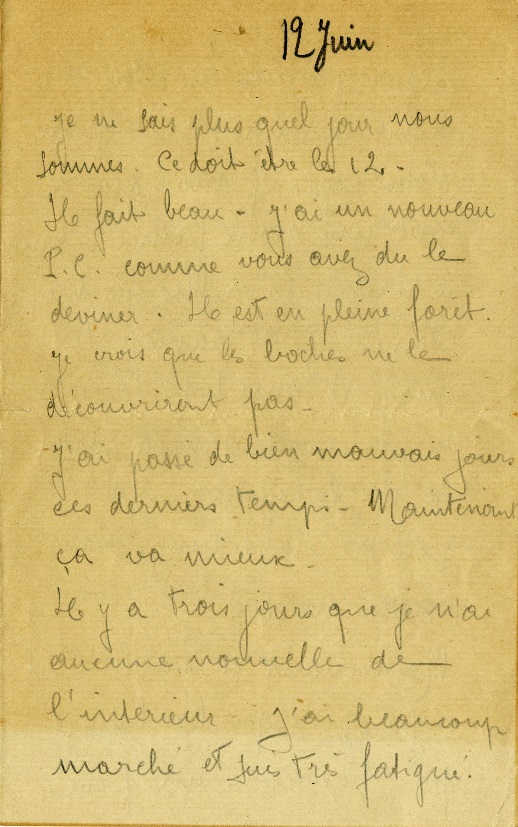

The second “guest” is Maurice Leclerc, a French soldier who was exposed to irritating gas in June 1916. On the next day he wrote on the accident in a letter to his family. The gas shell fell 20 meters in front of him, and Leclerc couldn’t avoid the cloud. His eyes and lungs were affected for a few hours but he was able to recover quickly. Listen:

A scan of his letter is available at: http://www.europeana1914-1918.eu/de/contributions/7384/attachments/78089?layout=0

The third account on chemical warfare comes from a British veteran, Arthur “Slim” Simpson. In an interview recorded in 1981 he recalls being exposed to irritating gas and suffering a few days from the effects. Listen:

The full interview is available at: http://www.europeana1914-1918.eu/en/contributions/5648.

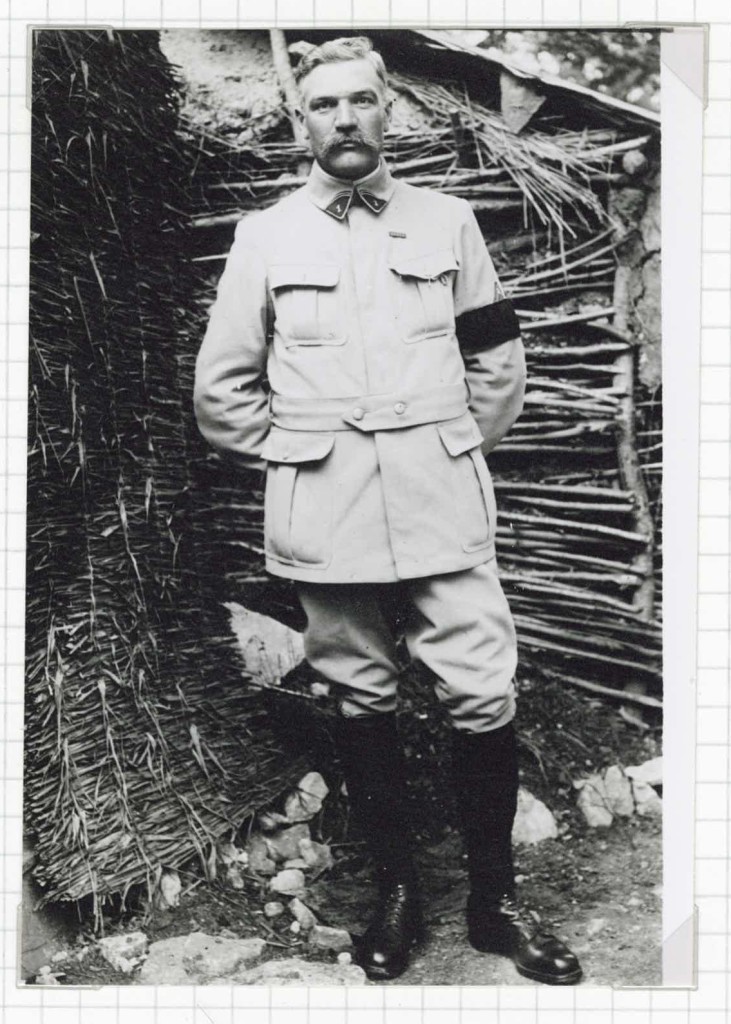

The last document is a letter from Guido Sampaolo (see episodes #1 and #4), dated 8h July 1915. He denounces a broad usage of poisonous gas from the Austrian army, as well as the lack of gas masks among Italian troops (he claims that in his sector only 2 masks every 15 men were available). Sampaolo also writes that the gas masks were not always effective, and could not ensure full protection for the soldiers. Moreover, they also had to suffer the awful smell of corpses: the enemy was occupying a ventilated high ground and didn’t allow the dead to be buried. Listen:

-Credits-

Editing: Eva Schmidhuber, Matteo Coletta

Voices in this episode: Hannes Hochwasser als Johannes Görtemaker, Matteo Coletta as Maurice Leclerc and Guido Sampaolo, Arthur Simpson as himself.

Jingle:

Music: Gregoire Lourme, “Fire arrows and shields”

Concept: Matteo Coletta

Voices: Hannes Hochwasser, Matteo Coletta, Roman Reischl, L.J. Ounsworth, Norbert K. Hund.