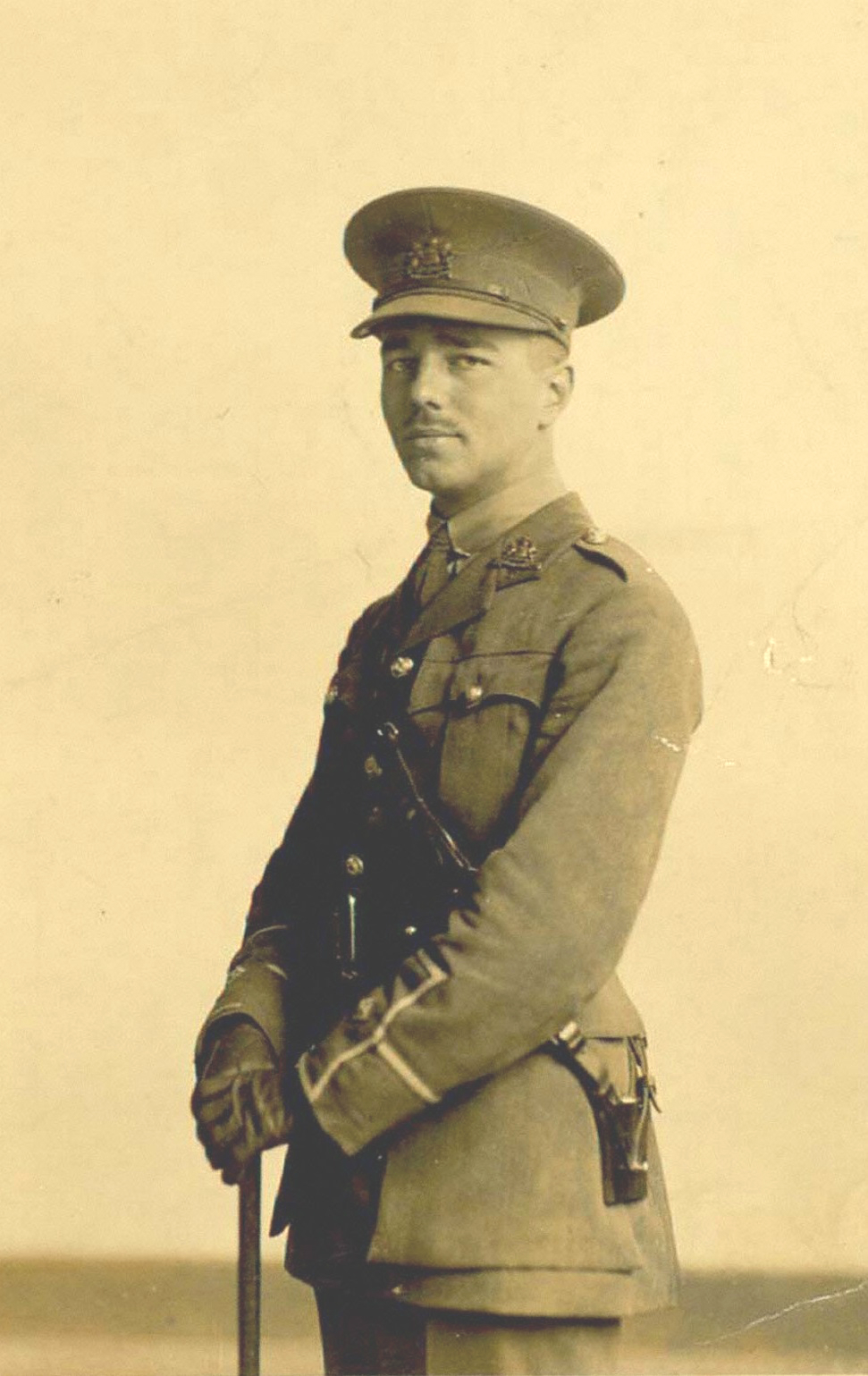

In Stimmen aus den Schützengräben #13 we deal once more with aerial warfare. The first document is an interesting letter written by Major Francesco Baracca on the 8th April 1916. Baracca was Italy’s top flying ace of WWI, with 34 confirmed victory. He was extremely popular during his lifetime, and became a legend after he was killed in action: it is said that Enzo Ferrari, founder of the luxury car manufacturer, took the „prancing horse“ from Baracca’s own emblem.

In the letter, Baracca gives a very detailed account of his victory over an Austrian plane. The duel took place on the 7th April 1916 above the Isonzo front (see episodes #12, #11, #5, #4, #1), not far from Medea. Baracca managed to dodge the machine gun bursts fired by the Austrian observer and reach a blind spot under the enemy’s tail, from which he could critically hit his opponent. The Austrian plane dived towards the ground and landed on a field, where it was immediately surrounded by a huge crowd. It was customary for the pilots who landed behind enemy lines to set their plane on fire to avoid its capture, but that time it wasn’s possible because of the wounded observer. Baracca writes: „The „Aviatik“ landed almost undamaged. It is beautiful, with a 200 HP engine, a good Austrian mashinegun (…) it’s one of the latest aircrafts, improved, for scouting and fighting. It can reach 145 Km/h (…). Near the jump seat the plane was all covered in gore, it gave a sad impression of war“.

The letter is permeated by those contraddictory feelings towards war. On the one hand, the fascination for aircrafts, the excitement of flying, the thrill of victory („I followed him down, screaming of joy“). On the other hand, sadder feelings as well as respect and compassion for the defeated („I spoke for a long time with the pilot, shaking his hand and conforting him, because he was very dispirited“).

The Austrian pilot, a 24 year Viennese, was almost unharmed, but the observer was severely wounded. Baracca was shot down two years later, on the 19th of June 1918. The exact circumstances of his death are still to be clarified. Some passages of his letters are available at: http://www.museobaracca.it/Francesco-Baracca/Il-mito-di-Baracca

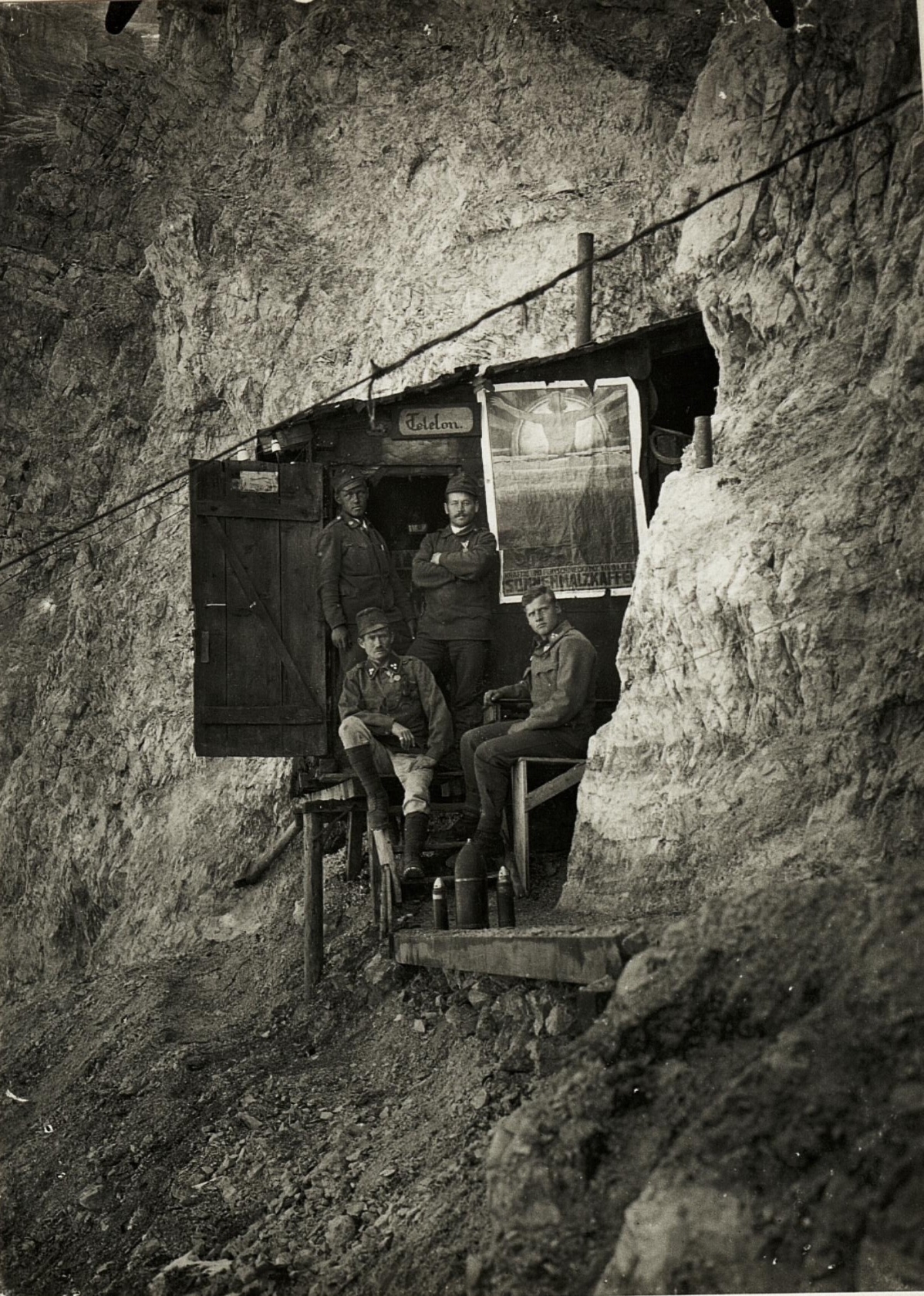

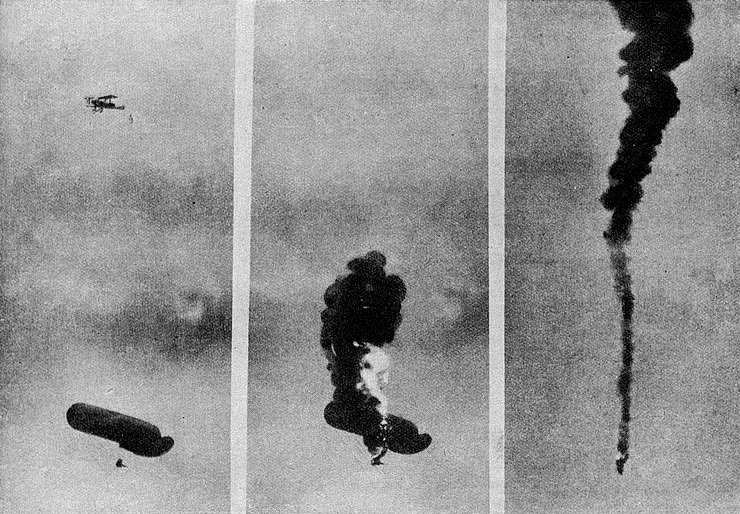

The second document is a letter from German soldier Johann Görtemaker (see episodes #5 and #12), in which he tells the destruction of a German tethered balloon. The observer could survive thanks to his parachute: a similar occurrence is related by French officer Emile Dupond in episode #3. The letters of Johann Görtemaker are available at: http://www.europeana1914-1918.eu/de/contributions/462

The last document of the week is an original audio interview with French officer Emile Dupond (see episode #3), who was assigned to a tethered balloon company. He remembers some interesting events which took place in April 1917, at the Chemin des Dames. Despite the weather conditions, his company was ordered to follow the advancing French infantry and observe the field. After a few kilometes the infantry couldn’t advance anymore, and the officers ordered to bring the balloon down. It was then dragged for a few kilometers by 150 men, who were struggling against wind and rain. The officers were afraid that the men could loose the grip on the ropes and abandon the balloon, so they asked a non-commissioned officer to remain in the gondola. They told the soldiers: „if you let go the ropes, your fellow is lost!„. Eventually, everything worked out fine, but it was an ordeal.

The recording has been cut, cleaned and edited to improve the sound quality. The full tape in its original condition is available at: http://www.europeana.eu/portal/record/2020601/attachments_120906_10243_120906_original_120906_mp3.html?

-Credits-

Editing: Larissa Schütz , Matteo Coletta.

Commentary: Peter Welzesberger

Voices in this episode: Hannes Hochwasser als Johann Görtemaker, Matteo Coletta as Francesco Baracca, Emile Dupond as himself.

Jingle:

Music: Gregoire Lourme, “Fire arrows and shields”

Concept: Matteo Coletta

Voices: Hanes Hochwasser, Matteo Coletta, Roman Reischl, L.J. Ounsworth, Norbert K. Hund.