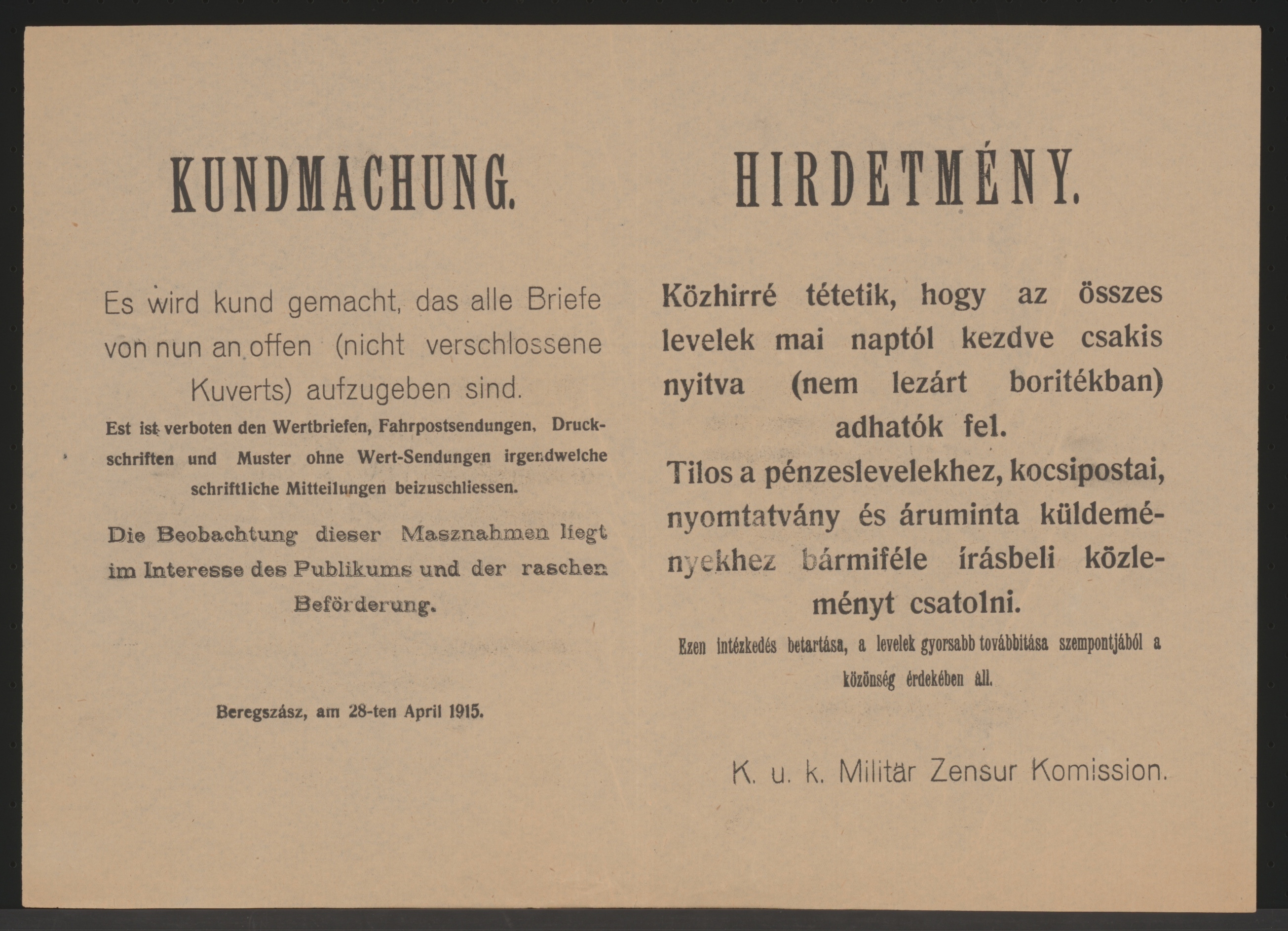

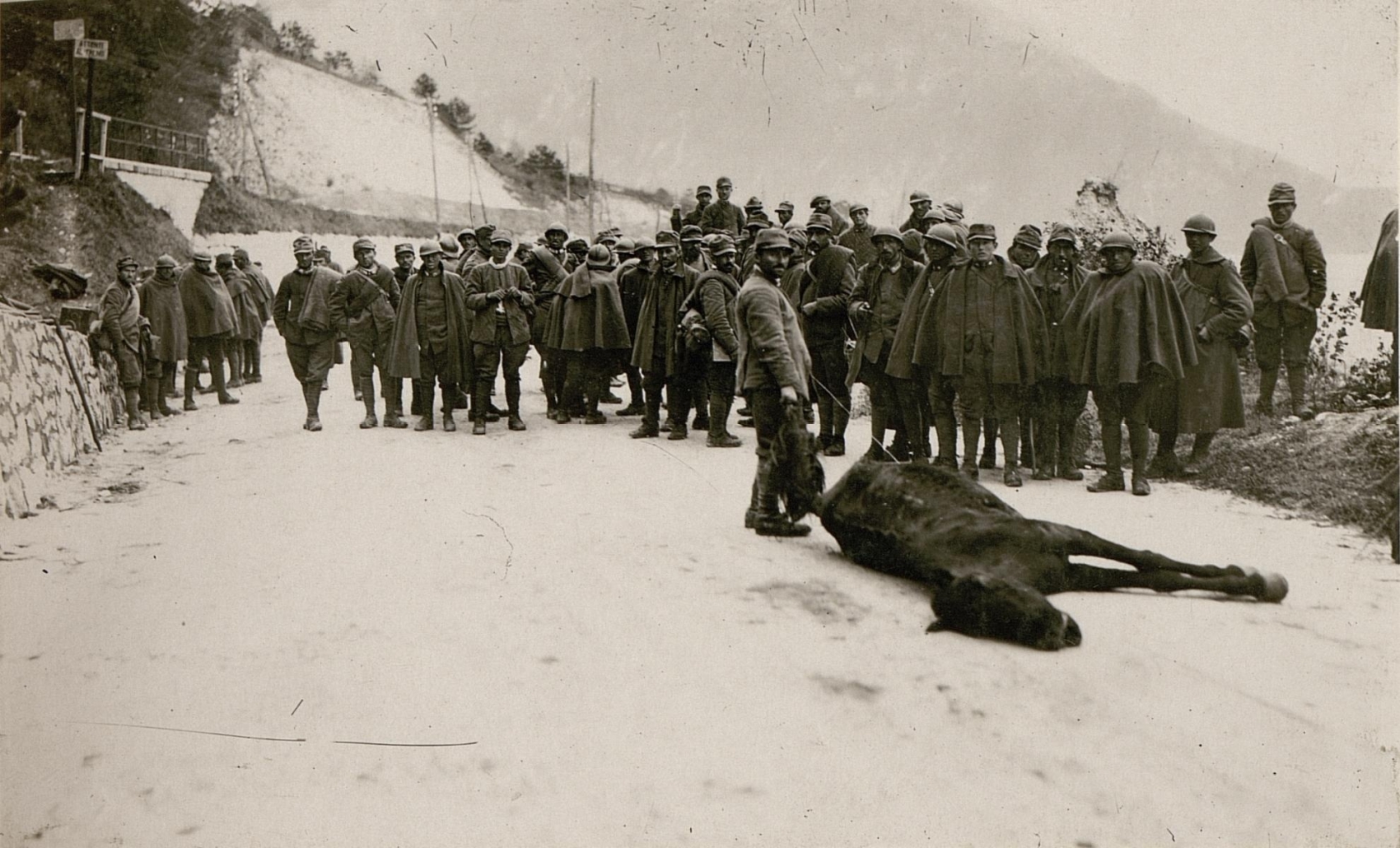

In Stimmen aus den Schützengräben #18 we deal with an often disregarded topic: animals at war. During WWI millions of animals were used for various tasks on all fronts. Horses were not only used by cavalry but also by artillery regiments to pull the heavy artillery pieces. Mules were also used to convey supplies, especially in the mountains. Dogs could have different tasks: sentry, scouting, conveying messages, finding casualties, providing psychological comfort as mascottes. Pigeons were also widely used to convey messages, with an astonishing 95% rate of success. This episode focuses on horses and mules, presenting different aspects of their life and death on the frontline. They were by far the most exploited animals: in 1917 the British Army alone had to buy 15.000 horses a month to mantain the number they needed!

The first document of the week is a letter by Johann Görtemaker (see episodes #5, #12, #13, #14 and #15) ), written in Flanders on the 12 August 1917. The German soldier tells to his parents: „in our previous positions we also had artillery barrages, but it has never been such a Hell as here. The Somme was surely not worse“. In that barren land full of mud and holes, artillery batteries had to be moved quite often to avoid counter-battery fire. Sometimes guns, men and animals would get stuck in the mud. „suddenly I fell with my horse, which sunk belly-deep into the mud. Hopefully the bavarian gunners finally managed to pull me from under the horse“. In such conditions, animals were sometimes enduring more than men: „Horses suffer the most, because they must remain for hours in one spot and they only get a small amount of fodder“. A transcription of the Görtemaker’s letters is available at: http://www.europeana1914-1918.eu/de/contributions/462

The second document is a passage from an interview with British Sgt Leonard J. Ounsworth (see episodes #1, #3, #7 and #8). As a soldier enlisted in an artillery regiment he was always in contact with horses, and he says the training of animals was even more important than that of men. When a cannon had to be moved teamwork between men and horses was crucial, because only with a well-coordinated effort it was possible (for exemple) to pull a gun out of the mud. The full interview can be downloaded at: http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/gwa/document/9404?REC=1

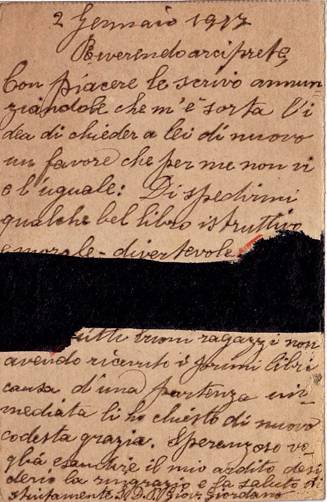

The third “guest” of the week is Italian Lieutenant Paolo Caccia Dominioni (see episode #15). We selected two interesting passages from his diary. The first is from an entry dated 20 September 1917. The officer mentions the presence of a dead mule exactly in the middle between two batteries, that stinks horribly because nobody wanted to bury it. The two gun crews are insulting each other while stating it is not their duty to bury the animal. During WWI, dead mules and horses were often part of the landscape. The second passage is taken from the entry dated 21 September 1917. Some mules got sick and died after being fed only rice (see episode #15), and Caccia Dominioni got into some trouble with the army. His comments are very sarcastic: when a men died, nothing happened, but for mules enquiries would be started and the whole bureaucracy would be involved. The war journal of Paolo Caccia Dominioni has been published under the title: “1915-1919. Diario di guerra“

The last “guest” of the week is French soldier Paul Lintier. He was enlisted in an artillery regiment and fought from 1914 until 15 March 1916, when he was killed in action. He wrote a book of memories (“Ma pièce, souvenirs d’un canonnier“) that was first published as feuilleton by the newspaper L’Humanité in spring 1916. The first passage depicts a sick horse, so emaciated that “one wonders, how the bones of his hips aren’t piercing his skin“. The second one tells of a wounded horse that had to be killed by the author with a shot in the head (“there is human suffering in the eyes of this beast“). The full book can be read at: https://archive.org/details/avecunebatterie00lint

-Credits-

Editing: Romana Stücklschweiger, Matteo Coletta.

Commentary: Matteo Coletta.

Voices in this episode: Hannes Hochwasser as Johannes Görtemaker, Matteo Coletta as Paolo Caccia Dominioni and Paul Lintier, Leonard J. Ounsworth as himself.

Jingle:

Music: Gregoire Lourme, “Fire arrows and shields”

Concept: Matteo Coletta

Voices: Hannes Hochwasser, Matteo Coletta, Roman Reischl, L.J. Ounsworth, Norbert K. Hund.