The 20th and last episode of Stimmen aus den Schützengräben completes the trilogy dedicated to War Poetry (see episodes #6 and #11).

The first text was written by German soldier Georg Britting: “Neujahrsnacht im Schützengraben”: http://www.britting.de/gedichte/1-076.html

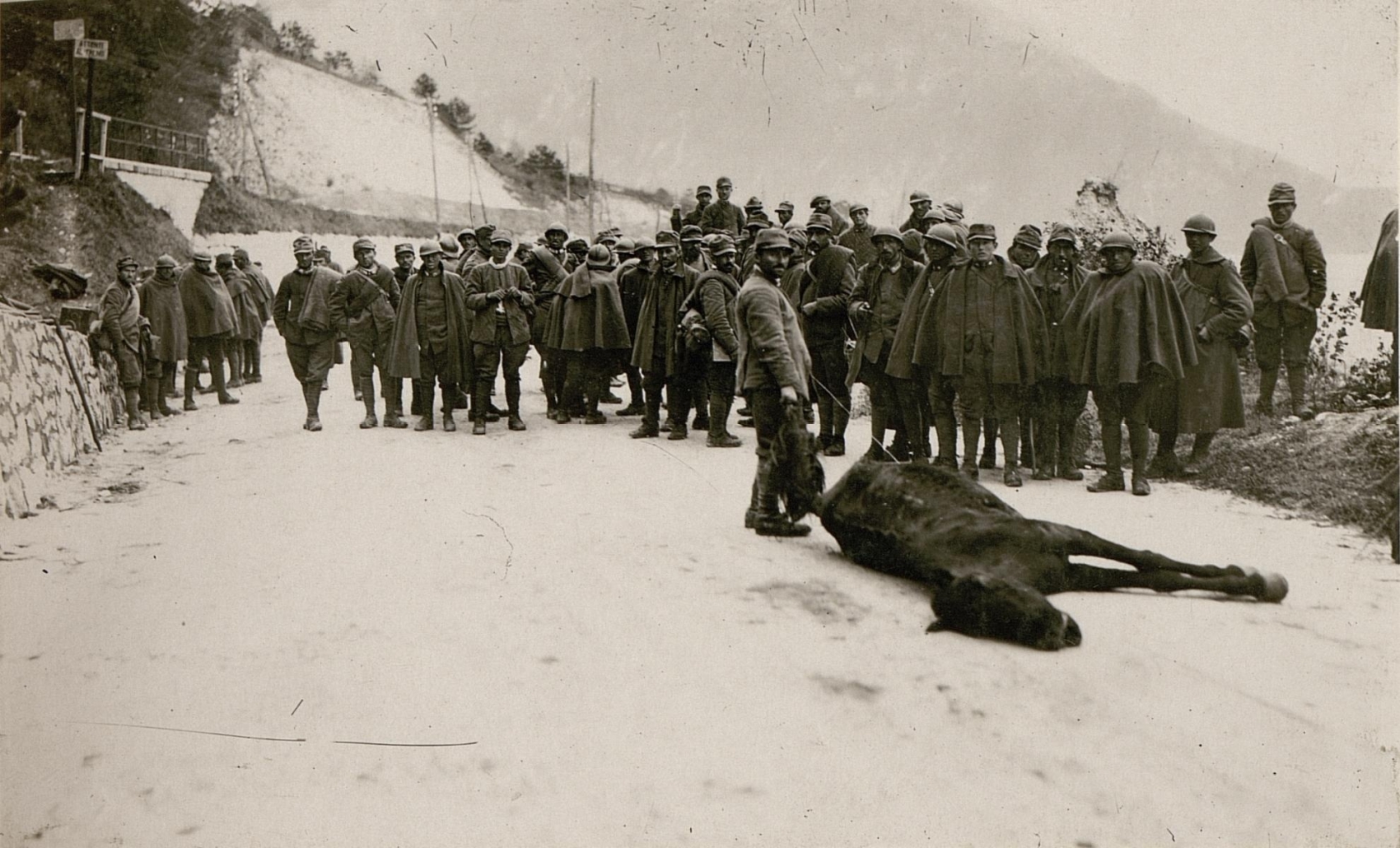

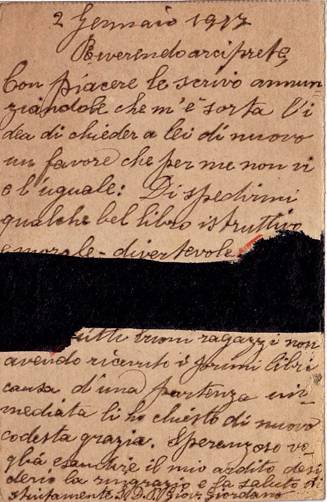

The second poem is “S. Martino del Carso“, by Giuseppe Ungaretti (see episodes #6 and #11):

“Di queste case,

non è rimasto che

qualche brandello di muro

Di tanti che mi

corrispondevano,

non è rimasto neppure tanto.

Ma nel mio cuore,

nessuna croce manca:

è il mio cuore,

il paese più straziato.”

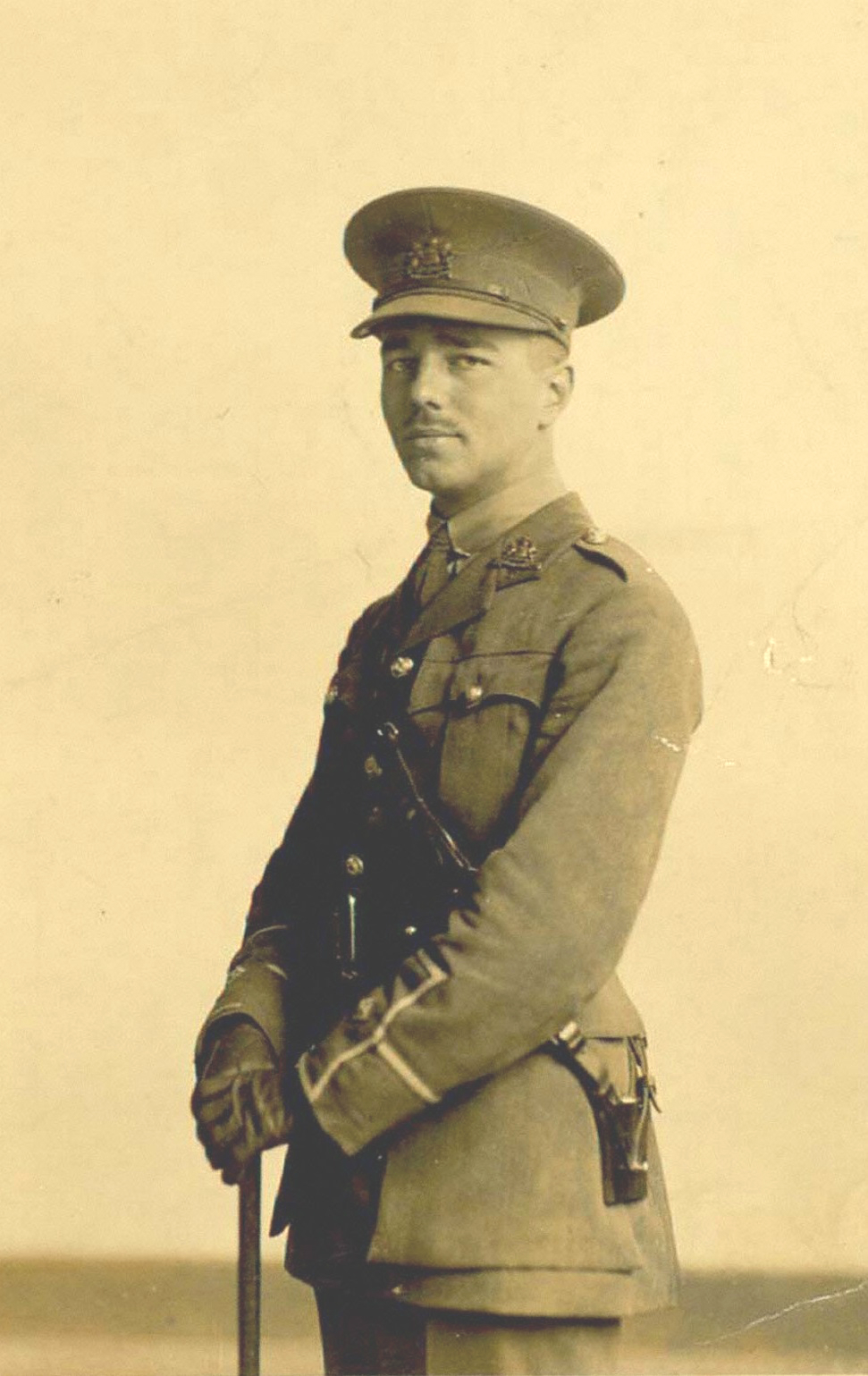

We already discussed British War Poets in Stimmen aus den Schützengräben #11. The third document of this week is one more Sonet by Siegfrieed Sassoon:

Trench Duty

Shaken from sleep, and numbed and scarce awake,

Out in the trench with three hours’ watch to take,

I blunder through the splashing mirk; and then

Hear the gruff muttering voices of the men

Crouching in cabins candle-chinked with light.

Hark! There’s the big bombardment on our right

Rumbling and bumping; and the dark’s a glare

Of flickering horror in the sectors where

We raid the Boche; men waiting, stiff and chilled,

Or crawling on their bellies through the wire.

“What? Stretcher-bearers wanted? Some one killed?”

Five minutes ago I heard a sniper fire:

Why did he do it?… Starlight overhead–

Blank stars. I’m wide-awake; and some chap’s dead.”

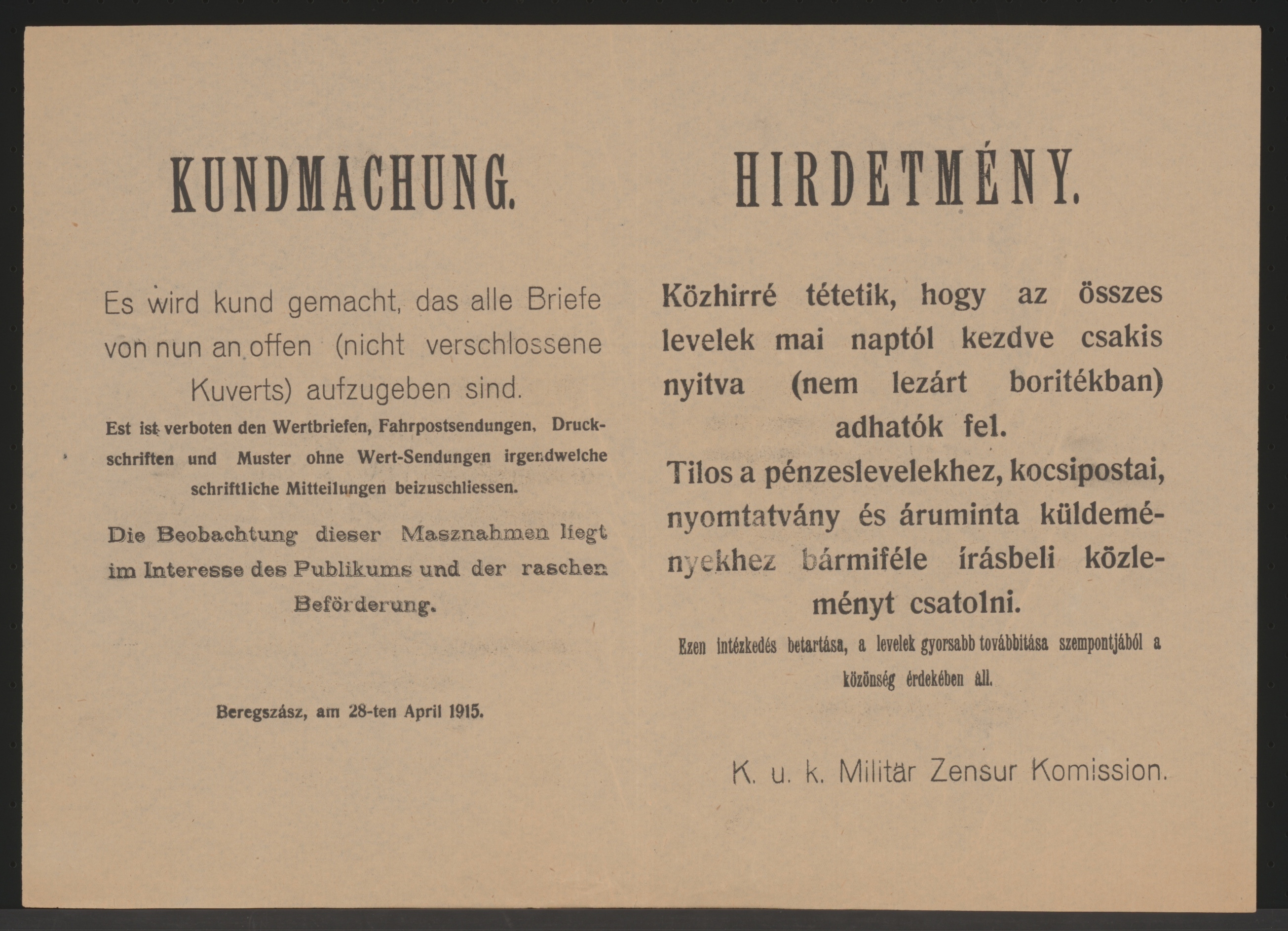

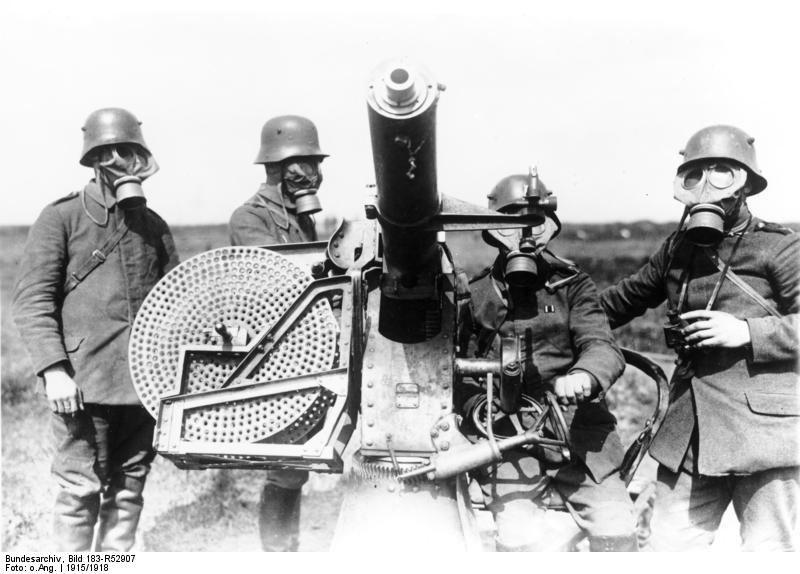

Most of the poems and other documents we presented during this project are against war. It must not be forgotten, however, that the conflict was often supported not only by part of the cultural and political elite, but also by many common citizens.

For some artists and poets, war and violence were an inalienable part of life and therefore of their artistic credo. A perfect exemple to clarify this point is the 9th point of the Futurist Manifesto written by Tommaso Marinetti and published in 1909 on the French newspaper Le Figaro:

“Noi vogliamo glorificare la guerra – sola igiene del mondo – il militarismo, il patriottismo, il gesto distruttore dei libertari, le belle idee per cui si muore e il disprezzo della donna.”

“We want to glorify war — the only cure for the world — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas for which to die, and contempt for woman.”.

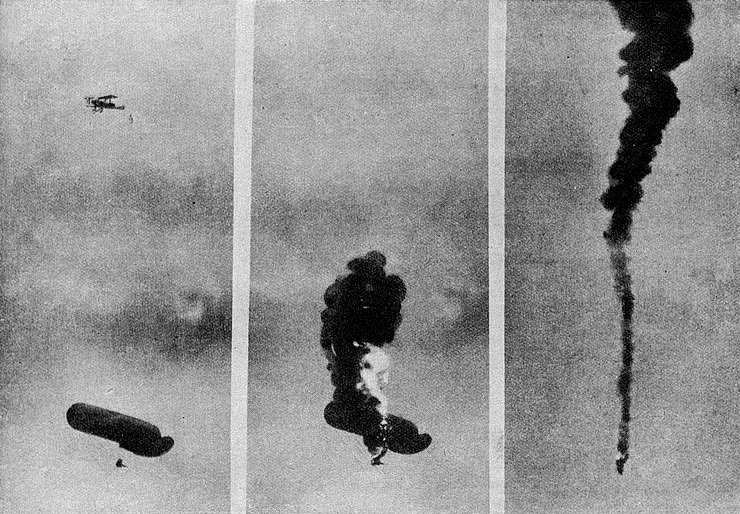

Among the many examples of poets who used war as poetical imagery we selected some verses by French soldier Albert-Paul Granier (Guillaume Apollinaire also did it to some extent, see episode #11). Granier became an airborne artillery observed. He was shot down and killed in action over the battlefields of Verdun on 17 August 1917, aged 29.

La guerre est dure comme une tempête,

la guerre est farouche et meurtrière,

comme l’Océan, par les nuits d’équinoxe où les vaisseaux perdus hurlent sur les écueils,

la guerre, soudain calme et dormante,

la guerre folle, sauvage et féroce,

la guerre est belle, dites, les gars,

la guerre est belle comme la mer !…

La tranchée est une vague pétrifiée,

une vague attentive et silencieuse,

bouillonnante et débordante de force.

Et, là-bas, les obus invisibles,

cataractants et foudroyants,

se heurtant aux blockhaus d’acier âpres et durs comme des brisants,

fleurissent en gerbes soudaines,

en hauts bouquets sifflants et fumants,

comme si un fabuleux raz de marée donnait du front sur la falaise.

Et, par-dessus, le ronflement des trajectoires comme le cri unanime de la mer.

We closed the episode with a poem written by German Soldier Karl Bröger. This source was kindly made available by the Brenner-Archiv (Universität Innsbruck). It is featured in: “Eberhard Sauermann (Hg.): Schützengrabengedichte. Online-Anthologie. http://www.uibk.ac.at/brenner-archiv/editionen/ged_wk1/schuetz_ged.html.”

-Credits-

Editing: Romana Stücklschweiger, Matteo Coletta

Voices in this episode: Hannes Hochwasser as Georg Britting, David Hubble as Sigfried Sassoon, Matteo Coletta as Giuseppe Ungaretti und Albert-Paul Granier, Matthias Falkinger as Karl Bröger.

Jingle:

Music: Gregoire Lourme, “Fire arrows and shields”

Concept: Matteo Coletta

Voices: Hannes Hochwasser, Matteo Coletta, Roman Reischl, L.J. Ounsworth, Norbert K. Hund.