[iframe src=“http://cba.fro.at/268742/embed?&title=false&socialmedia=true&subscribe=true&series_link=true“ width=“100%“ height=“250″ style=“border:none; width:100%; height:250;“]

Stimmen aus den Schützengräben #10 deals with alpine warfare. The Alps are a natural barrier between the north of Europe and Italy. Their narrow passes and valleys have a great strategic relevance, and they have been crossed through the ages by a plethora of invading armies. Between the 19th and 20th centuries many forts and defensive works were built in northern Italy to defend those precious access points. The Austrian Empire erected about 50 forts in the Italian Tirol („Welschtirol“), which were designed to work together as a defence line but also to resist for a long time if the supplies were to be cut off. The Kingdom of Italy also build several forts to protect the border with Austria (the so-called Sbarramento Agno-Assa) and Switzerland (the so-called Linea Cadorna).

When Italy declared war to Austria in May 1915, the original plan was to take advantage of the surprise and cross the mountains quickly. The lack of competence and organisation of the Italian headquarters brought the operation to failure, and gave way to attrition warfare. Military commands on both sides were obsessed by the control of high ground, and troops were deployed on passes and summits. Sometimes the fighting took place at incredible heights, e.g. the Battle of San Matteo (3678m).

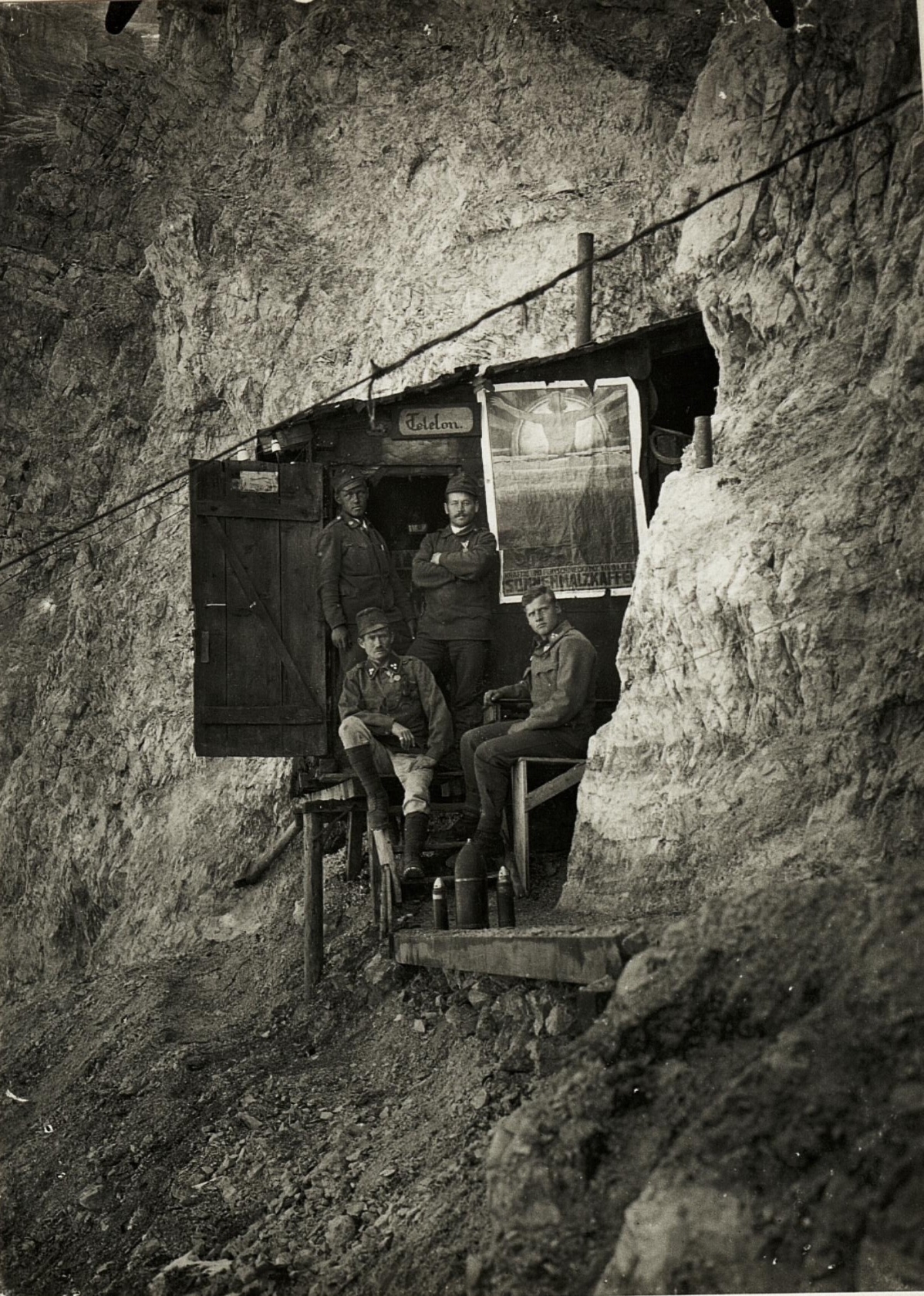

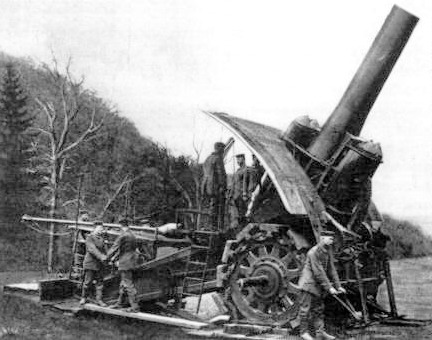

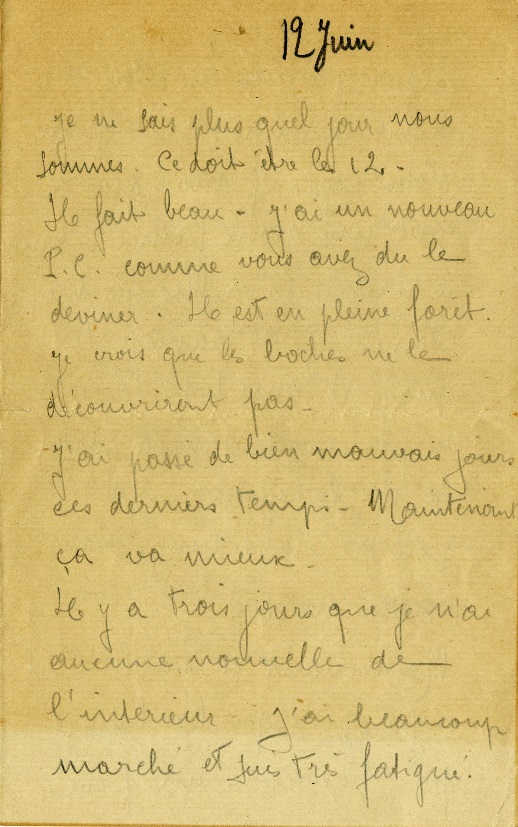

The war in the Alps took many different forms. Where possible, roads (like the Road of the 52 tunnels) were built to carry artillery and supplies with the aid of mules. In several occasions tunnels were dug under enemy positions, to put mines under them: e.g. on the 13th March 1918 an astonishing 50.000 Kg of TNT blew under the Italian lines on mount Pasubio. However, the battlefield was often too unaccessible to allow the huge deployments of men and means that were typical of WWI. On some summits and observation points the garrisons consisted of only a few dozen men, and skirmishes between patrols took the place of massive assaults. In such conditions, the men accomplished real alpinistic exploits, and Nature was often more dangerous than the enemy: on one single night, between the 12th and 13th of December 1916, about 10.000 soldiers’s lives were taken by avalanches on the Alpine front.

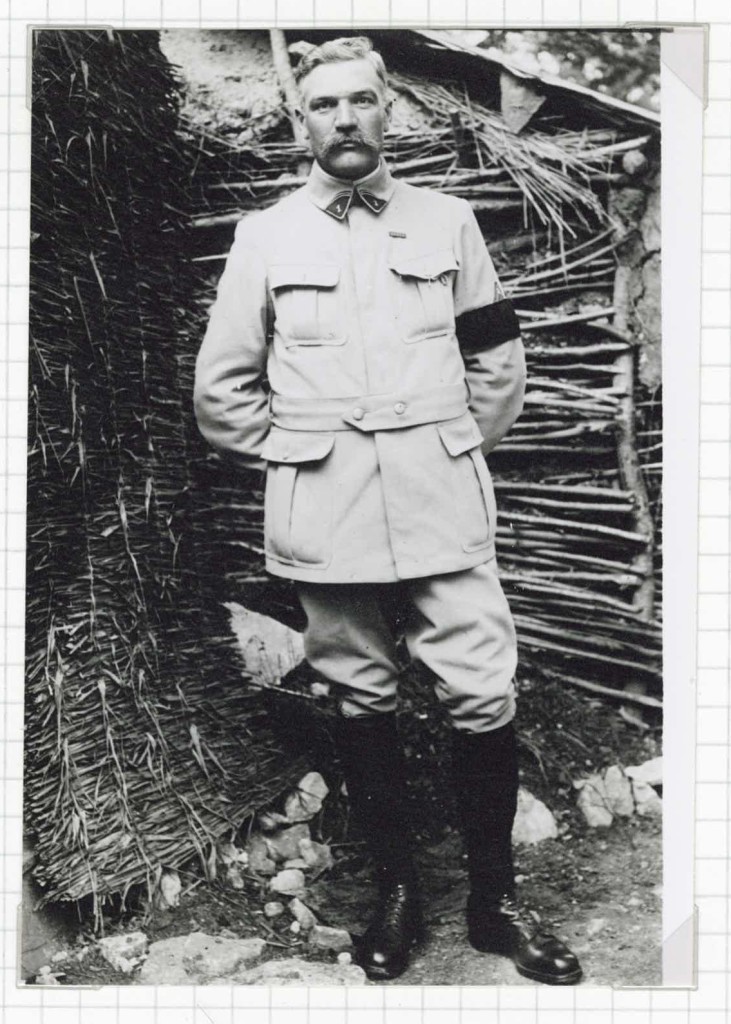

The first „guest“ of this week is the Austrian Kaiserjäger Ludwig Pullirsch (the Kaiserjäger were a light infantry corp recruited mostly in the alpine regions of southern Austria). In a short extract from his memories he relates of an exhausting march, where he had to carry a 30 Kg backpack and climb a height difference of 1600 meters. These events took place in May 1916, on the Adamello-Presanella mountain range. Pullirsch survived the war and wrote several diaries, some extracts have been collected by his son at: http://www.menschenschreibengeschichte.at/index.php?pid=30&ihidg=13948&kid=1181. The full memories have been published under the title „Hineingeboren“, ISBN 978-3-940582-07-2.

The second „guest“ of the week is Giacomo Pesenti, an Italian Alpino (the Alpini are the oldest elite corp of mountain troops in the world. During WWI those soldiers were mostly recruited in the alpine regions of northern Italy) . Pesenti volunteered for the army in May 1915, as soon as the war broke out between Italy and Austria, and was awarded the silver medal of honour for his courage. Many years after the war he wrote his memories to pass down the legacy of those terrible events. In the selected passage he relates of a 3-days watch in a ice hole on the Thurwieser pass (3480m), together with 30 other soldiers; the cold was extreme and the enemy was hiding 50 meters below. The short extract comes from the book „La Grande Guerra in Lombardia“, by Giuseppe Magrin, and it is set between 1916 and 1917.

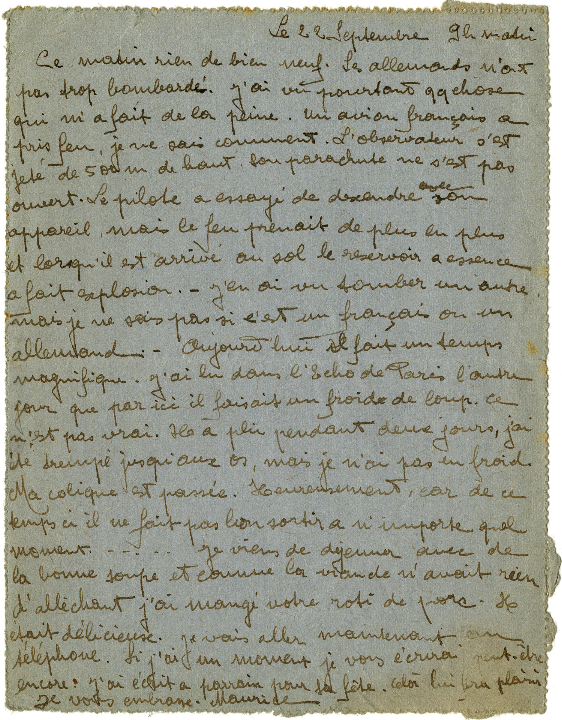

The third guest is Austrian soldier Thomas Bergner. He Fought the war on the Italian front and died in 1926, aged 38, as a result of the wounds and illnesses contracted during the war. In 1915 he was sent to the Isonzo valley, in present-day Slovenia, and in an entry dated 20th of July he gives an account of his first day in the new positions. The artilleries were shooting and the mountain was quite hostile: falling rocks were a constant threat.

The last passage is taken from the book „Un anno sull’altipiano“, by Emilio Lussu (see episode #8). In spring 1916, while coming back from a scouting mission on the Asiago plateau (ep. #2), Lussu met an Italian colonel. The conversation between them quickly became surreal: the colonel criticised harshly the strategical decisions of Italian high commands: what was the point of defending the top of a mountain, if no artillery was there to protect the valley? The enemy could have ignored it, and advance quickly towards the south. But the high commands are the same everywhere: eventually the Austrian army lost time and men trying to get the „key position„, and lost its precious chance.

-Credits-

Editing: Laura Leitner, Matteo Coletta.

Commentary: Laura Leitner.

Voices in this episode: Alex Huemer as Ludwig Pullirsch, Matteo Coletta as Giacomo Pesenti and Emilio Lussu, Roman Reischl as Thomas Bergner.

Jingle:

Music: Gregoire Lourme, “Fire arrows and shields”

Concept: Matteo Coletta

Voices: Hannes Hochwasser, Matteo Coletta, Roman Reischl, L.J. Ounsworth, Norbert K. Hund.