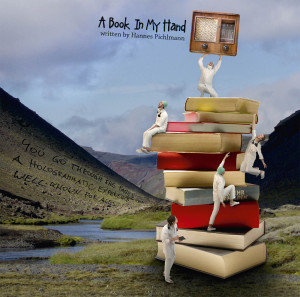

> Sendung: Artarium vom Sonntag, 11. Januar – Das komplette brandneue Album der Wiener Band SoundDiary – eine in vielerlei Hinsicht außergewöhnliche Abenteuerfahrt durch die Glücksgefühle und Gefährdungen des postmodernen Nomadentums auf der Suche nach der Seinsinsel zwischen Sinn und Zusammenhang. Meine Reaktion aufs erste Durchhören dieses akustischen Bewusstseins-Roadmovies erfand sich in folgenden Worten: „Ich kenne zur Zeit keine österreichische Band – Blank Manuskript einmal ausgenommen – die den nötigen Scheißdrauf hat, ein derart authentisches Progressive-Rock-Konzeptalbum herauszubringen, dem man zwar immer anhört, dass es 2014 produziert wurde, von dem man aber meinen möchte, seine Kompositionen stammten aus der Blütezeit von Genesis & Co.“ Allein das schon eine Empfehlung 😉

Doch es verbirgt sich noch weit mehr hinter der gefälligen Oberfläche eines stimmigen Musikalbums, das auch durch gelungenes Crowd-Funding produziert und im Eigenverlag fairöffentlicht werden konnte:

Doch es verbirgt sich noch weit mehr hinter der gefälligen Oberfläche eines stimmigen Musikalbums, das auch durch gelungenes Crowd-Funding produziert und im Eigenverlag fairöffentlicht werden konnte:

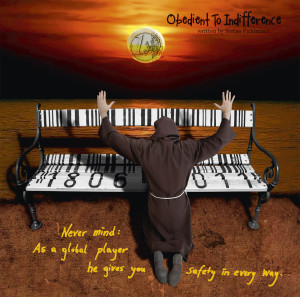

Philosophische Fragestellungen zum Beispiel – und Reflexionen über das Verhältnis des Individuums zur Welt – in Gestalt einzelner Mitmenschen, gesellschaftlicher Gegebenheiten oder verinnerlichter Moralgebote, die Songtexte sprechen da für sich.

Ich in Beziehung UND unabhängig – dieser rote Faden ist das Konzept des Albums und zugleich wohl auch programmatisch für die Interessen der Bandmitglieder. Nicht nur, was kommunikative Publikumsberührung in Verbindung mit größtmöglicher künstlerischer Freiheit anbelangt, sondern gewiss auch in persönlich erlebten Versuchen, neue Formen zu entwickeln fürs Zusammensein der Gegensätze – mit einander, in der Welt – und – zwischen sich selbst! Aufbrüche ins Ungewisse…

Ich in Beziehung UND unabhängig – dieser rote Faden ist das Konzept des Albums und zugleich wohl auch programmatisch für die Interessen der Bandmitglieder. Nicht nur, was kommunikative Publikumsberührung in Verbindung mit größtmöglicher künstlerischer Freiheit anbelangt, sondern gewiss auch in persönlich erlebten Versuchen, neue Formen zu entwickeln fürs Zusammensein der Gegensätze – mit einander, in der Welt – und – zwischen sich selbst! Aufbrüche ins Ungewisse…

Endlich wieder einmal, textlich wie musikalisch, ein Gesamtkunstwerk, dem man die emotionale Echtheit und das individuelle Engagement seiner Schöpfer_innen (!) abnehmen kann, möcht man lauthals aufjubeln. In Zeiten wie diesen, wo fast jede Neuerscheinung allzu affensichtlich aufs Arschloch des Marktes schielt, um sich sogleich in irgendeiner Pose zu verfieberzapferln zwecks ihres besseren Verkaufs. So erbrechenbar wie Fastfood, Fernsehen und jede andere Mainstream-Prostitution. 😛 Hallelujah! Oder so. Jedenfalls wissen wir jetzt wieder, warum wir ein Konzeptalbum wie dieses hier lieben. Weil es uns auf eine handwerklich gut zubereitete Zauberreise mitnimmt – durch die wechselvollen Zustände und Zwischenwelten unseres Daseins. Weil wir uns in ihm wiederspiegeln, in unserem Kampf um die eigene Sinnstiftung, inmitten von Größenwahn, Niedertracht und Volksverhumpfung. Eben weil es etwas zu sagen hat – und das auch tut. Eine Message (jawohl), die Fragen und Antworten im Zwiegespräch mit sich selber belässt – und die einen so auch zum Selbstdenken der eigenen Welt anregt. Was ließe sich über ein Kunstwerk wohl Schöneres sagen? Lehnen wir uns also zurück in unsere Leben und genießen wir diese Erfahrung:

Endlich wieder einmal, textlich wie musikalisch, ein Gesamtkunstwerk, dem man die emotionale Echtheit und das individuelle Engagement seiner Schöpfer_innen (!) abnehmen kann, möcht man lauthals aufjubeln. In Zeiten wie diesen, wo fast jede Neuerscheinung allzu affensichtlich aufs Arschloch des Marktes schielt, um sich sogleich in irgendeiner Pose zu verfieberzapferln zwecks ihres besseren Verkaufs. So erbrechenbar wie Fastfood, Fernsehen und jede andere Mainstream-Prostitution. 😛 Hallelujah! Oder so. Jedenfalls wissen wir jetzt wieder, warum wir ein Konzeptalbum wie dieses hier lieben. Weil es uns auf eine handwerklich gut zubereitete Zauberreise mitnimmt – durch die wechselvollen Zustände und Zwischenwelten unseres Daseins. Weil wir uns in ihm wiederspiegeln, in unserem Kampf um die eigene Sinnstiftung, inmitten von Größenwahn, Niedertracht und Volksverhumpfung. Eben weil es etwas zu sagen hat – und das auch tut. Eine Message (jawohl), die Fragen und Antworten im Zwiegespräch mit sich selber belässt – und die einen so auch zum Selbstdenken der eigenen Welt anregt. Was ließe sich über ein Kunstwerk wohl Schöneres sagen? Lehnen wir uns also zurück in unsere Leben und genießen wir diese Erfahrung:

„What counts and what matters can neither be said nor written, composed, performed or played.“

> Hinweis: Einen Vorgeschmack auf dieses Kunnstwerk (nebst allerlei musikalischen Assoziationen) gibt es in unserer illustren Nachtfahrt-Sendung „Winterschlaftraum“ 😉